Casey Reas

Casey

Reas

Interviewed by

Demian Conrad

and

Rob van Leijsen

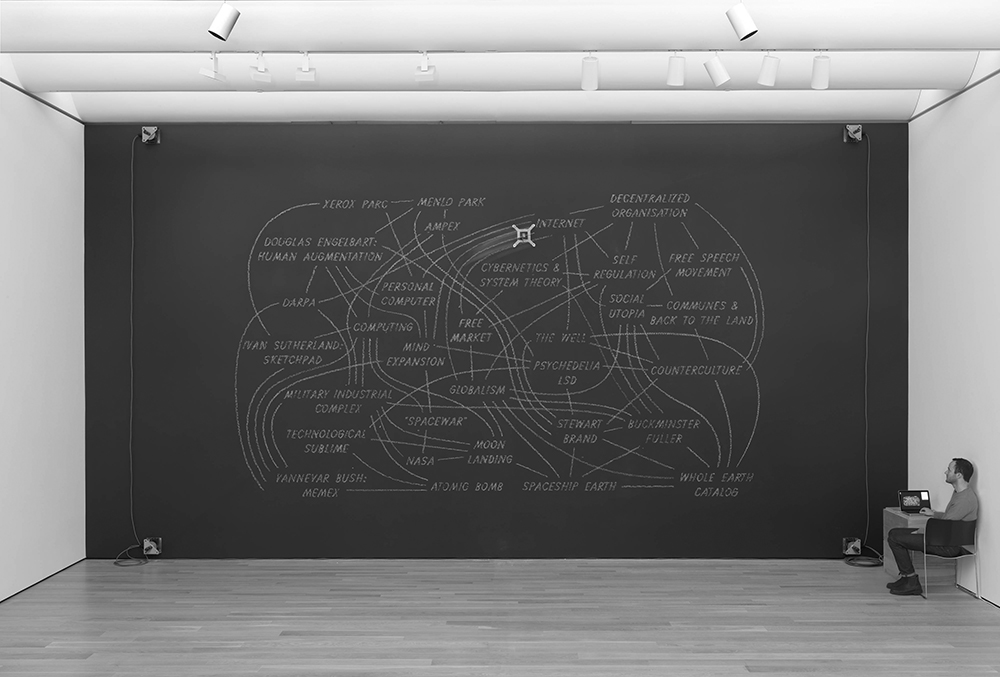

<Casey Reas>18 (aka Casey Edwin Barker Reas, b. 1972, Troy, Ohio) lives and works in Los Angeles. He holds a Masters degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Media Arts and Sciences and a Bachelor's degree from the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning at the University of Cincinnati. In 2001, Reas created Processing, an open-source programming language and environment for the visual arts, in collaboration with Ben Fry. His software, prints, and installations have been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions at museums and galleries in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Reas’ work ranges from small works on paper to urban-scale installations, and he balances solo work in the studio with collaborations with architects and musicians. His work is also part of both private and public collections, including the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Reas is currently a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles.

It’s a question that’s being asked more frequently these days. Since his name first appeared in 2013 on a website set up as a public resource for software developers, his work has been the subject of intense scrutiny on both sides of the Internet. As a professional software designer, Casey Reas designs tools and techniques for software development. But on the web-based project management platform called Asana, he writes and maintains the design guidelines for projects. The latter is a job that requires intense focus and rigorous attention to detail. Reas holds two professional degrees: a B.S. in computer science from Cal Poly Pomona and an M.S. in computer science from San José State University. Over the course of his career, he’s designed computer apps, worked on the systems architecture for a couple of dot-coms and most recently helped launch Google+ into the world. He’s worked with startups and large corporations — and he still does. The Casey Reas Experience In fact, Reas left the Googleplex and moved to Amsterdam for a while last year to work on the new version of Gmail. And as you’d expect from a former Cal Poly Pomona computer science major, he’s well versed in all things code. If you want to get a peek at some of his software design process, Google Plus will show you how it all works. You can go to Reas’ homepage, sign up for an account, and then simply open a project in G+. (That’s a lot of text to write, and a bunch of clicking to do as well. I’ve provided a link to G+ right at the top of this article. The reason for the design guidelines (you’d think Google’s engineers would know better than to let such a large, well-paying company fail at so fundamental a task, but then again you’d think wrong) is so that everyone can have a common experience when working on any Google project. Reas’ process starts with his own research, then moves through a series of drafts. Reusing a lot of code that’s been written before means less time spent writing new stuff. In recent years, Reas’ project-sharing approach has come in for quite a bit of criticism. On the one hand, you have to admire anyone taking his project to such a level. On the other hand, it strikes me that a lot of the criticism focuses on Reas’ ideas, process and the need for the guidelines. Those things are just the way he designed his projects — and you know what, that’s fine.

D.C.Hi Casey, thanks for participating in this project. To begin with, we’d like to know how you started using creative coding in your design practice.

C.R.Well, Ben Fry, my partner and co-creator of the Processing project, and I both had degrees in graphic design. I had studied at the University of Cincinnati (Ohio), and he had studied at Carnegie Mellon University (Pennsylvania). I attended design school in the early to mid-1990s, which was a time of change. We were moving away from a hand-based, craft system to using software. I learned a lot of the original techniques of drawing type by hand, and how to develop these little systems manually. However, we were also learning to use the really early versions of some of the design softwares that have now become the standard, such as Illustrator and Photoshop . Consequently, I would say that I had a bit of a hybrid education that combined the more traditional manual methods and software techniques.

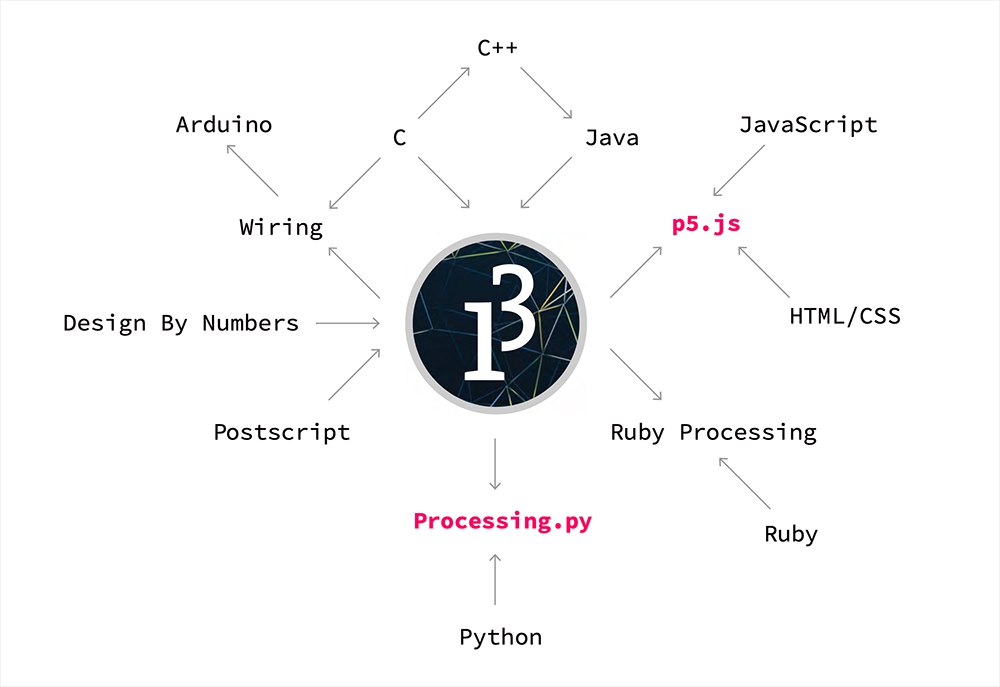

C.R.When I graduated, the World Wide Web was becoming an international phenomenon. In 1995, I began applying what I had learned about publication design and typography to the Web. It was the first time I felt I was working in a way that felt compelling—writing HTML and CSS —and for me this was the bridge. Once I started to think about onscreen type and typographic systems, I decided I wanted to do more of that, and that was when I began to learn code. I really hadn’t done that before. At the time, designers who were coding were generally using programs like Macromedia Director . It was like a multimedia system, where you would bring in media elements, like images, and then apply code to those. Ben and I were both interested in working more directly with code as a medium. That led to our working with languages like C++ and Java , which had remained primarily confined to computer science, and were not adapted for the visual arts.

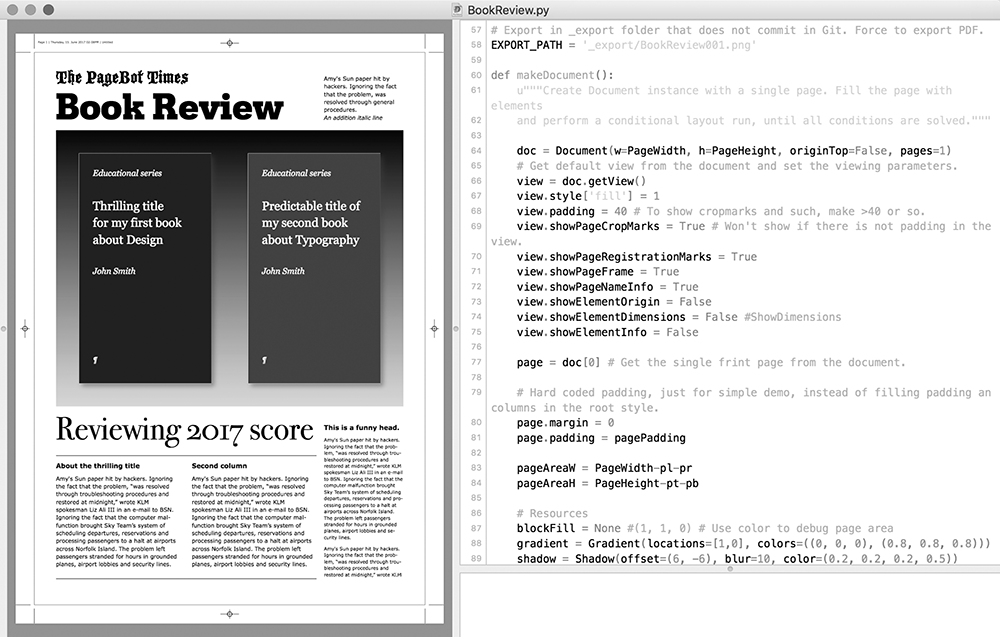

C.R.The concept behind Processing was to adapt design education and design ideas to a method of thinking and making using computer science, to create a coding system we felt was more approachable and accessible for people who are primarily visual. We had visual artists and designers, and even, to a lesser degree, architects, in mind as potential users.

C.R.When you learn coding, you need to learn it within a domain, and that domain traditionally consists of working with text and mathematics. Consequently, the idea of Processing was to change the domain in which you learn to code, and let you explore code within a visual framework.

C.R.The design education that I received in Cincinnati in the 1990s was very much rooted in the Bauhaus, and what had happened in Basel in the 1970s, as well as at Yale, which had also been heavily influenced by Basel. My teachers had been trained in the same manner.

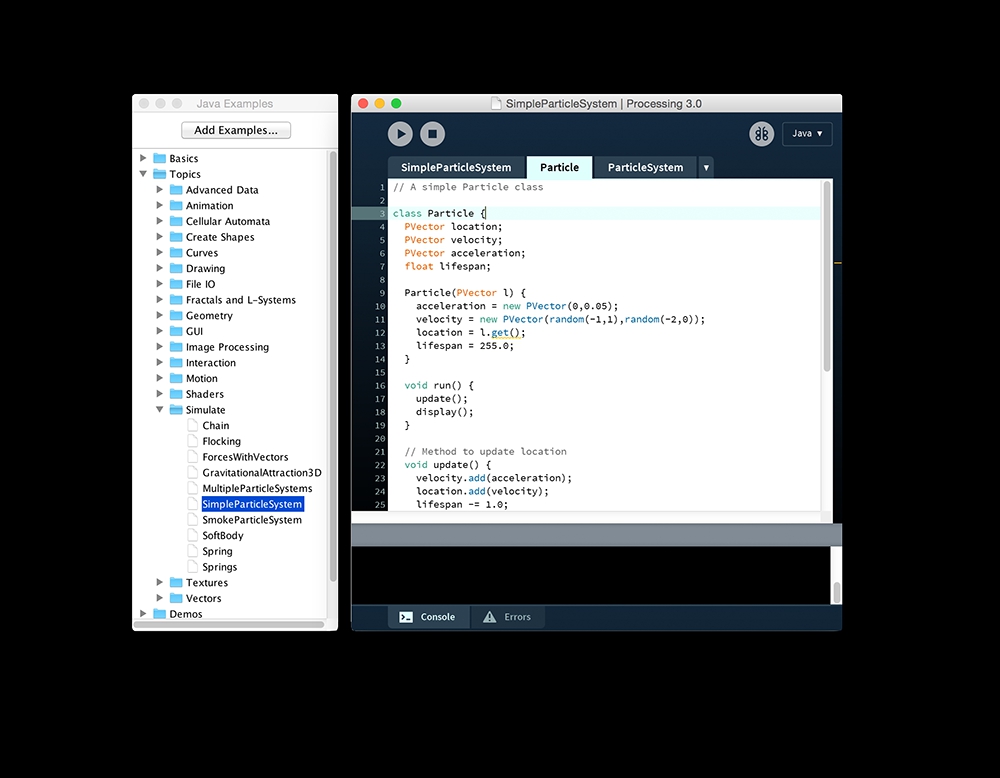

C.R.When we started working with Processing , I was influenced by these teaching methods as well as the design books of the 1960s and 1970s. We tried to think about a way of learning to code where you could practice and study following those foundational traditional design education techniques. The Processing project grew directly out of a coding initiative written by John Maeda called Design By Numbers. It was a coding environment that was very approachable for visual designers, but it had a lot of constraints. You could only make programs that were 100 × 100 pixels, and black and white was the only option. Ben and I had assisted John with that project, we had taught workshops with it, and we were very enthusiastic about its potential, but we wanted to expand and extend it, in order to be able to work with color, in full screen, and all those sorts of things. That was essentially the inception of the Processing project; it was extending everything we thought was amazing about Design By Numbers, but bringing it more into a complete, visual environment.

R.v.L.Can you tell us a bit more about the environment and the situation in which you and Ben developed this platform? Since you were already graphic design graduates at that point, had the educational environment provided an incentive to build this or not?

C.R.I think we both graduated around 1996 and worked as designers for a number of years, before going to graduate school. I worked in New York at the time, at a small company doing work on the Web, and Ben worked in California. I think he might have worked for Netscape for a while, then we both met for the first time at the MIT Media Lab . Ben started there in 1998, and I started in 1999. We both went there to study with John Maeda, who was a professor there, and had founded a research group called the Aesthetics and Computation Group [ACG]. The Aesthetics and Computation Group occupied the space in the Media Lab that had previously been used by Muriel Cooper’s Visual Language Workshop, before her untimely death, and also built on a lot of its ideas. Consequently, it was imbued with the feeling of carrying on some of that legacy and a sense of exploration. It was there that Ben and I started working together with John Maeda on Design By Numbers.

C.R.It was also the birthplace of Processing . I think we made our initial sketches in June of 2001, which was at the very end of my time there, but Ben continued on as a PhD student during Processing ’s early years. When I graduated, I moved to Northern Italy and began teaching at the Interaction Design Institute in Ivrea, north of Turin. I also started doing workshops around Europe, while Ben was still at MIT. We developed the software together over the course of many years, and released the first official version in 2005, I think, but it had been released informally as of 2001 through a lot of workshops, and to anyone who asked us.

C.R.I would say the Processing project grew absolutely and directly out of the culture of the MIT Media Lab , and then the community around Processing and the people using it just continued to expand from there.

C.R.One of the fundamental ideas behind it was to take different code libraries we had access to at MIT, and make those available to people outside of any institution. Another initial concept behind the project was to enable people to be able to work quickly with the code. For example, you typically needed twenty to forty lines of code to make a line move across the screen at the time, but Processing would only need five. It could handle some of the infrastructure that a computer science person knows how to build, but a beginner coming from the sphere of the arts does not, providing a bridge to enable such people to begin working directly with code.

C.R.A really important early idea of the project was sketching with code. In addition, as a designer, when you start working, you often do so without knowing the destination. You do research, and develop ideas, and you work out ways to get you where you want to be. We wanted that process to be possible with code. The original idea behind the Processing language was to make it more accessible for sketching, and to think through writing small sketches in code.

D.C.It’s interesting to hear that you derived some inspiration from the legacy of Muriel Cooper and the Visual Language Workshop. She was probably the first to try and bridge the gap between engineering and design. Were you fortunate enough to have met her?

C.R.I didn’t have the opportunity, but other people did. John Maeda knew Muriel Cooper, he had had some interactions with her as a student at MIT. Also, David Small was someone who had been a part of both research groups: he had been working on his PhD when Muriel passed away, and he continued on with John Maeda—he was a direct bridge.

C.R.Our research group [ACG] was located in the exact same space in the Media Lab where Muriel’s group had worked, and all of their research documents and papers were still around. My own personal story is that I was working in Boston as an intern at a design studio, and I attended a design symposium at the Media Lab, probably in 1993. It was there that I saw David Small and Yin Yin Wong present demos that had been created in the Visual Language Workshop.

C.R.That was my lightning moment, when I saw what I wanted my future to be. I saw what I was doing in design, what I knew about design, and the direction in which I wanted to be moving, so my original intent was to apply to study with Muriel Cooper. Unfortunately, she passed away before I completed my undergraduate work, but then I had the luck of meeting John Maeda, and I was able to study with him.

C.R.The Lab was not a large place. There’s a line of continuity from when it was first originated as the Architecture Machine Group, before becoming the Media Lab in 1985, and a lot of people who knew and loved Muriel Cooper were still at the lab at that time. I think that her legacy lived on through the individuals that she had worked with and had mentored.

R.v.L.Earlier on, you mentioned the workshops you did with the Media Lab, but also abroad. Did you adapt your teaching methods between the two? How important was the feedback of your students in the development of the software?

C.R.It was really important. We developed the software through teaching workshops and we always made adjustments each time we held one. Those modifications we made to the software were very important. I think the subsequent adaptations in the way we taught were even more critical, namely in the method we used and the order in which we presented things.

C.R.For instance, I remember doing a brief two-day workshop in Paris. On the first day, we started introducing sine and cosine mathematics, as a way of creating motion. For us, that was really just the basics, it was a technique that we were excited about, and had been using for such a long time, so we didn’t realize that there was a steep learning curve with that, and that oftentimes, for students from design backgrounds, mathematics is not something that either comes naturally or is particularly loved. Consequently, experiments in trying to study animation through mathematics were quickly eliminated from the one and two-day workshop platforms.

C.R.That’s just one example, but I think there were lots of more subtle ones, and many other examples of how the curriculum evolved at the time. I think when you go to a computer science class and you start learning code, there’s a certain set of priorities, which in my opinion, are very different from the priorities I have in my classrooms.

C.R.For me, it’s always about the digital media that’s produced and created. The primary objective is not the efficiency of the code, or other technical details. Accordingly, the curriculum changed rapidly over the first few years, and, I think, continues to change.

R.v.L.So, right from the start, the open-source platform was really a key element in the development of the software?

C.R.Yes, one of the important early decisions was to make what we call “libraries.” Ben and I realized that we were in a bottleneck and getting in the way of how people wanted to expand and extend Processing . Ben and I primarily focused on visual media. We don’t really have an expertise in audio or other areas of media in which other artists and designers like to work. So, we developed a library system that allowed people to extend Processing in their own way. Now, there’s well over 100 libraries which have extended Processing into other domains in which people have expertise. An important thing about the library system is that people can create them in their entirety, author and maintain them, then give them back to the community. It’s a way of getting engaged, without needing to delve into the complete source code. They are isolated pieces of source code that individuals can develop and share with other people. The libraries, I think, have been the primary way in which people contribute to the community, and also the means by which the project has expanded beyond its roots.

R.v.L.Would you call it a kind of co-authorship?

C.R.Well, I think it’s a co-authorship in terms of the larger frame of the project. I think the library authors really are the autonomous or complete authors of those contributions of theirs.

D.C.You mentioned in an interview that the project was half engineering, and half community building. Those are two areas of expertise that a designer doesn’t learn in school, and that they currently have to pick up by themselves. How did you acquire this expertise, and how did you develop it? What was the most difficult aspect of this for you as a designer?

C.R.I think one thing that’s important to clarify is that Ben Fry, my collaborator, is the primary software engineer of the project. He is better at those things than I am. He actually was, I think, a double major, or a computer science minor, while I really didn’t have any technical expertise in coding until I started learning, after I earned my undergraduate degree.

C.R.However, I think we developed a lot of our skills and knowledge by learning as we went along. In terms of community building, we put a lot of energy into that, but I don’t think that we were necessarily skilled at it. People had a desire to collaborate, and to come together and share knowledge. We put some really minimal resources in place, and people built on that with a lot of energy. I think the original forum was a place where people truly gathered, before Facebook, Twitter and such.

C.R.One idea behind being an open-source project was that people really shared. Someone would ask questions, and someone else would take the time to explain and write some code. That’s still happening on the forum, but at that time, I would say it was a small and pretty close-knit community.

C.R.As the Processing project expanded and became more international, that single close-knit community spread out. Now, there are a lot of more localized communities being formed and developed. We started the first Processing Community Days a few years ago, and the second year, we made it international. There were almost 100 events all around the world, across every continent. Local organizers made their own days for their own communities. I would say that the period from around 2002 to 2006 was one when it felt almost like a unified international community created around the forum. After that, it began to disperse and became something different.

C.R.Another thing that’s been really unexpected with Processing is that it was originally written as an university-level and art school-level introduction to coding for artists and designers, but lately it’s being used more and more in high schools and middle schools, at least in the United States. It’s oftentimes used in other areas as well, like in a mathematics class, for making visuals for math, or in a physics class, for small physics demos. So Processing has found its way into areas beyond our original expectations.

C.R.When the project first began in 2001, it was really heavily integrated into the World Wide Web, and Java was able to play in all the browsers through Java applets. You would basically just be working in the Processing editor, you would click export, and it would then build a Java applet and an HTML file. You could put that on any server, and then display your work through the web. That was the aspect of it that allowed us to grow, and for other people to find and see it. It was the community aspect of sharing your work with other people, and getting feedback about that work. People in design communities would have their own websites and post their own experiments, and then communicate through the forums. I think, to a large extent, that’s a thing of the past. Still, it was the way the project found a community, and an audience in the beginning. Of course, the decline of Java applets on the Web is one of the main reasons for this change. As a result, Lauren Lee McCarthy started the p5.js project in 2013. You might say that it’s been a way of bringing the Processing coding style back onto the Web, and that’s why it’s a separate and very energetic community.

R.v.L.You mentioned Processing being used in a variety of educational programs, did you also see different outcomes there?

C.R.I think each kind of class has its own kind of assignments, as well as outputs that are oriented towards what that particular educator has in mind. Originally, a lot of the Processing assignments, and exercises as well, were more like traditional basic graphic design assignments. Now that’s really no longer the case: we see every kind of visual style.

D.C.You’ve been teaching at UCLA, a major university, for a while. We wanted to know how they currently perceive creative coding, and what their pedagogical strategy is regarding creative coding?

C.R.UCLA is a huge university, but the School of Arts and Architecture is a relatively small community. Our department, which is called Design Media Arts, numbers twelve faculty members, and probably about 180 students, so everybody knows each other.

C.R.I don’t think there are going to be any radical shifts regarding creative coding happening anytime soon. One thing that’s evolved over time is that our introductory class in coding for artists and designers, called Interactivity, is now a required course for all of our students. This has been the case since around 2006. Even if somebody wants to move into typography and specialize in print design, this class is a required part of the program.

C.R.The course has evolved a lot, in order for it to work for students who are not necessarily interested in the topic, or perhaps don’t know yet that they are interested, and we don’t have any plans to change that. Right now, we find this to be fundamental knowledge for the students. I think the idea is that, as a university-level design program, we want them to have some degree of understanding of how software is constructed, how the software that they’re using is put together, because these students are going to be using computers constantly for their work, and they’re going to be using high-level tools like InDesign , Illustrator and Photoshop .

C.R.In that sense, the class is very much a general introduction, and it has become a lot less technical over the years. It includes less coding, but encourages the students to be original and inventive with the small amount of coding that they do learn. The class is very media-focused, so our students have a wide range of aims and aspirations. Some students are interested in video, animation, photography, typography, etc., so the class I teach on coding touches upon all of those subjects over the course of the term. For instance, we do a project that focuses on looping photographic images, almost like an old zoetrope, but integrating interactivity. We also do a project that allows them to load different typefaces and set them in a way that involves interactivity.

R.v.L.What obstacles to coding, if any, do you perceive when it comes to your students? Do they have difficulties starting out, or with accessibility? How do you deal with that?

C.R.It really isn’t an issue where there’s a lot of friction or conflict. I think all the students know they will have to deal with code, and perhaps they kind of prepare themselves. I have been readjusting the class now for many years to try and ease them into it.

C.R.I know all the students can do it, they’re all capable of doing it, it’s just a matter of enabling them to gain confidence, and kick-starting an interest in creative coding. At the beginning of each course, I’m very upfront in letting my students know that I’m aware that this might be their only experience with coding, and that they may never want to look at another line of code again when the class is over. As long as we’re all open about that, things seem to flow rather smoothly. Focusing on the media they’re making and its visual and interactive aspects hopefully provides them with the necessary motivation.

D.C.Have you ever been approached by other schools, perhaps through your foundation, for suggestions on how to integrate Processing and coding into an academic curriculum?

C.R.That happens mostly for lower grade levels, but not at the university level. We have a part-time Director of Education at the foundation now, Saber Khan, who is a high school teacher who holds open office hours and puts on events and series called the Creative Coding Festivals. He leads the initiative of interacting with educators. In addition, we have started a series of interviews with educators.

C.R.Over the years, I’ve written two books with the intent of sharing what I do in my classroom with everybody else; a longer textbook published by the MIT Press, followed by a book that’s much shorter and more casual, intended for younger people, that was originally published through Make magazine, also, I’ve always shared my syllabi online.

C.R.Other independent sites have a multitude of classes, with different syllabi, OpenProcessing , for example. I feel that people in the community have always been open about sharing their assignments and exercises, and one can look around and select from what they’re interested in when they develop things. Different institutions have taught coding with Processing for long enough that they have now developed their own internal ways of doing it, with their own syllabi, and they kind of pass it on from person to person. There was a time where I might have known most of the schools that were working with Processing , but now I have no idea. It seems like whenever I travel somewhere, I learn about new places using it. I guess nobody really knows exactly to what extent it has spread around, and where and how it’s being taught, but I would be interested in finding out.

R.v.L.When you were building the software at the MIT Media Lab , did you have the impression that you were subverting the establishment, or that you were doing something that was appreciated and welcomed in the sphere of graphic design, or design in general for that matter?

C.R.In the beginning, we were really making something for ourselves, to help us with our own work, to do our own sketching, something that we could use to teach. Honestly, my initial aim for the project, in addition to those two things I mentioned, was to initiate introductory coding classes within design schools everywhere.

C.R.Personally, coming from a design program, I was frustrated that my professors didn’t have any interest in computation, and did not see what software could do and make possible when used as a medium for design. It was actually a goal of mine to show what was possible. When I was at design school, a program for digital design was launched, separate from graphic design, because the graphic design professors disdained computers. However, I think that the program only existed for a short time, before it kind of became one discipline. Consequently, I definitely set out to think about code as a future area of design, and wanted that to be a part of the design curriculum.

R.v.L.So you mean that design departments should be much more inclusive, instead of relegating coding to the sidelines, separating it from the core graphic design courses?

C.R.I think that the idea of students having exposure to code, and an opportunity to explore it is exciting. One thing I’ve noticed is that sometimes, the students who don’t expect to enjoy it, are paradoxically the ones who actually create the best work. Sometimes it can just open up a range of possibilities that weren’t there before they had the opportunity to work with code. Another way I always frame it, is that, even if you’re not going to be a coder, even if it’s not going to be essential to your work as a designer, having some degree of literacy in this area facilitates your collaborations with other people.

C.R.I think the pragmatic truth is that, as a designer, you’re often working in teams, or working on projects for the Web; with UI and UX, you’re often working with people who are implementing that, and this enables you to have an understanding of what’s involved in moving your design into a piece of software for an app or for a website. The degree of literacy acquired from having some exposure to code can be really helpful in collaborations. There are different paths that can open up for someone if they learn a little bit of coding.

C.R.As design moves onto the Web more and more, and continues to evolve within a space of interfaces, applications and software, it becomes essential for designers to work with code, to gain some exposure and a level of introduction to coding, along with the skills necessary to work with those areas of design.

R.v.L.Designers today who are working independently, doing web-based work, are very aware of their limits, the need for collaboration, and understand what programming has to offer them. You can’t make it without any collaboration, and even if you specialize in web projects, you cannot substitute the extent of a professional programmer’s expertise.

C.R.Everybody needs help with coding, from time to time, even the most advanced coders. The more you learn about coding, the more you get a sense of where your own personal boundaries might be, and when it’s worthwhile to spend months learning something new, or when it’s better to find the right person to commission to handle that. I still need assistance with my own work. Sometimes I’ll hire somebody to write a shader, for example, because shader coding is not something that’s a part of my expertise.

D.C.How do you perceive the creative coding community at the moment? Would you call it a movement? How do you think it will evolve?

C.R.One thing I see is that software is far more powerful in 2020 than it was twenty years ago, when Processing was created. I think it can be difficult to take a student who is used to working with video editing or animation, and bring them into a space where we’re just drawing lines on a screen.

C.R.My entire design education basically consisted of composing lines for a few years, but now software can do extraordinary visual things, rendering styles, and high-end animation techniques. So how do we bring people back into an environment where they’re making these very minimal elements with code? I think that’s a challenge, at least for me, but a lot of these high-level visual environments in animation also have scripting languages embedded in them, which is something that’s always been a part of design tools.

C.R.You take an environment like Processing , which is just a text editor, versus a really extensive interface that has scripting capabilities. I think this goes all the way back to the precursors of multimedia environments, to things like Hypercard, which were environments where you would script on the elements; this, I believe, led to Macromedia Director , which was a whole generation’s primary environment for code work. In my view, the contemporary version of that is the Unity software, largely used within gaming programs. That’s one area, another is node-based coding platforms, things like Max, and there’s a lot of people who start teaching code with those kinds of node-based flow control programs. Then there’s the paradigm represented by Processing ’s pure text code.

C.R.As I see it, we have these three different areas to choose from when it comes to introducing coding concepts to our students. At the moment, I’m continuing to proceed with text-based coding, because I think this is the most general. The method we apply at UCLA consists of teaching the fundamentals of text-based coding, in Processing or p5.js , then students apply what they’ve learned to other areas. So students go and they work with Unity for game design, and some students move forward and dig really deeply into Java Script for web-based work. The idea is to learn coding fundamentals, which then enables them go further, into more specific domains.

C.R.I don’t feel that students necessarily need to continue working with Processing over the entire course of their education, or throughout their careers. I do that, and some other people do as well, but I’ve always thought of it more as a gateway. I think learning within the context of the Web through Java Script can also be a really good way of learning code. During the last twenty years, so many different tools have come out for designers to learn coding.

R.v.L.To follow up on this, do you perceive any visual influence of coding in advertisement campaigns, or on other visual outputs that now embrace coding solutions?

C.R.I think that the interesting thing about a lot of these high-level tools is that these scripts are often encoded into an interface where you check this or that box, and then it runs this really complicated script that somebody has written to generate something visual. More and more, a lot of these fundamental algorithm s continue to be added to different animation tools. You can more easily see the result of an algorithm being applied through a program like AfterEffects than if someone wrote the code directly.

C.R.I see it everywhere in design, from a logo system that might be kinetic, or an instance randomly chosen from a thousand different variations. Still, I don’t feel that it’s a norm or a dominant way of working. Maybe there’s a few dozen different studios from which you would expect that work to come. Yet I’m hopeful that this kind of work will continue to grow because I just find that it looks fascinating.

D.C.What are your plans for Processing ? Where do you want to take this project in the future?

C.R.The Covid pandemic has allowed me to work on an aspect of the Processing project that I have been thinking about for a long time. The software has always been completely free and open source, but a certain amount of the educational material is trapped in publishing contracts. So my current mission is to make a new modular series of tutorials that will be completely free, open, and accessible. It will include a web version, a book version, and a version that you can print and bind easily at home.

C.R.Another priority is the Processing website, which has been stalled for a number of years, along with the efforts to internationalize it. We are working right now with a design studio to rebuild it from scratch, and the idea of making it translatable is a priority. I really want it to be translated into Spanish first, along with many other languages, to make it even more accessible to global and international communities. The p5.js project has been informing a lot of my own approaches to Processing . Lauren’s work in building community and prioritizing access has allowed me to see a new path forward for the Processing project. That’s my current vision.

Practices + Economics

Design Practice

Emilie PilletYes. Our first collaboration was for a project I did at ECAL, an animated poster. I created a pattern in Illustrator and he saw the possibility of rendering it more dynamic with code. That got me interested in how code could mesh with my design practice. When I was working on my diploma project I learned some basics, but unfortunately I quickly forgot it all because I did not practice enough. So now I’m learning again, and I will see where it leads. I am on the lookout to see how creative coding can be implemented in my design practice, but it takes a long time to master a programming language.

Field of Graphic Design

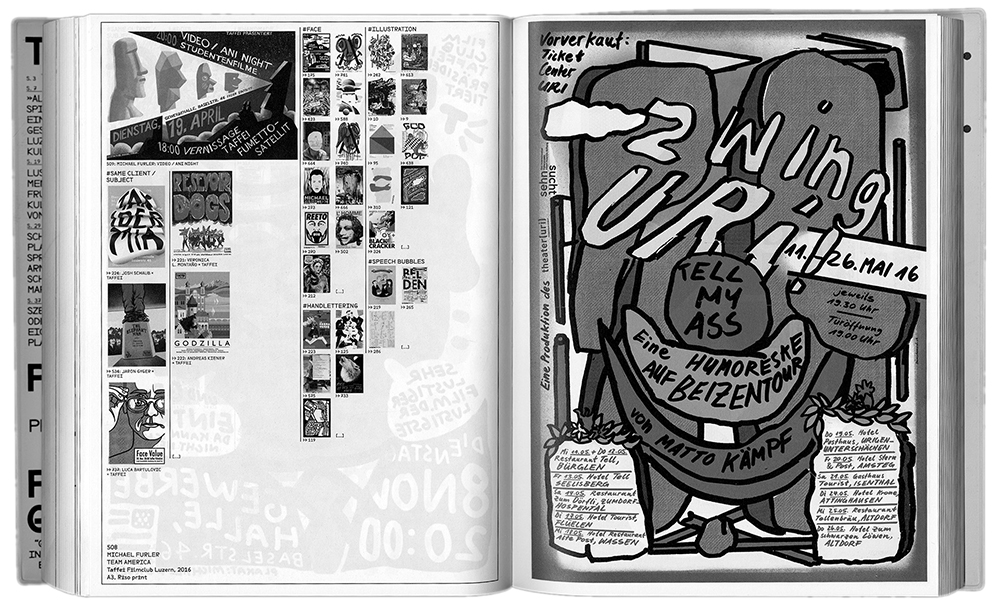

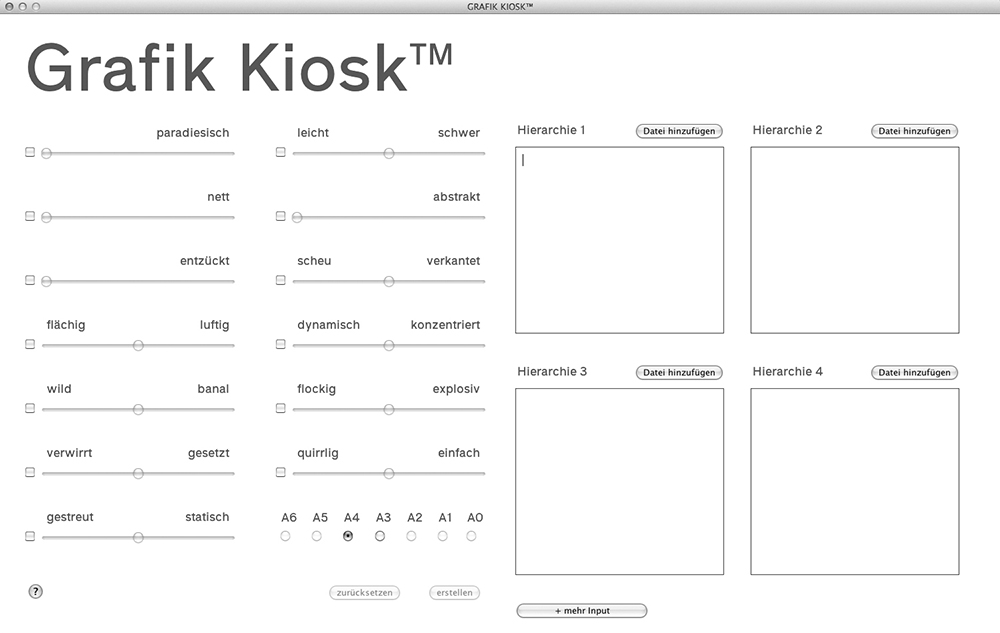

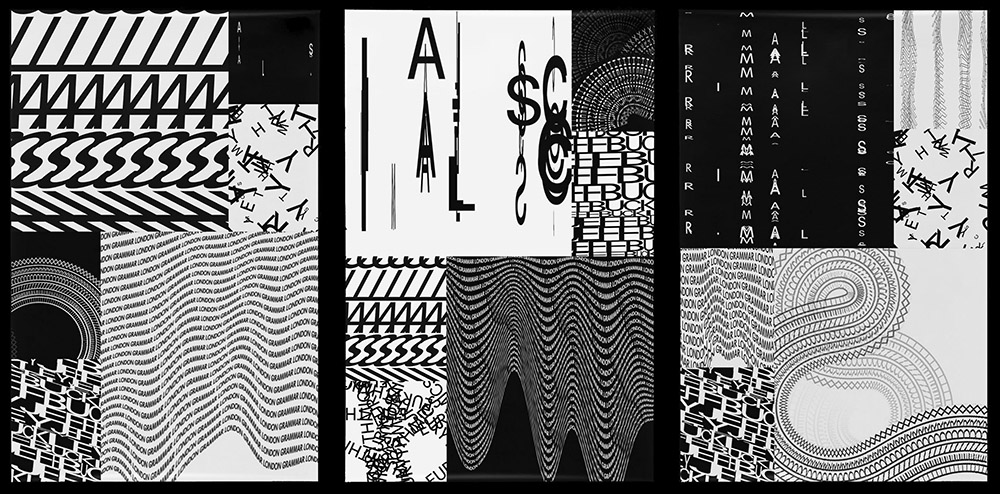

Samuel WeidmannGrafik Kiosk was my thesis project with Jonas Hegi for our Bachelor’s Degree in Visual Communication at ZHdK, back in 2011. While I was in school, I already became interested in future issues relating to the profession of graphic designer. This continued during my internship at Lehni-Trüb, where they were already thinking about process automation in the field of graphic design, such as templates and PDF to book. Jonas was an intern at NORM, and he was interested in design systems. At some point, we both met Raphael Koch, who, along with Urs Hofer and Gina Bucher, created a software called Rokfor for generative design through templates. We were quite interested in those types of processes, from a machine that allowed you to design and print your business card at the Zurich train station, to software built for design.

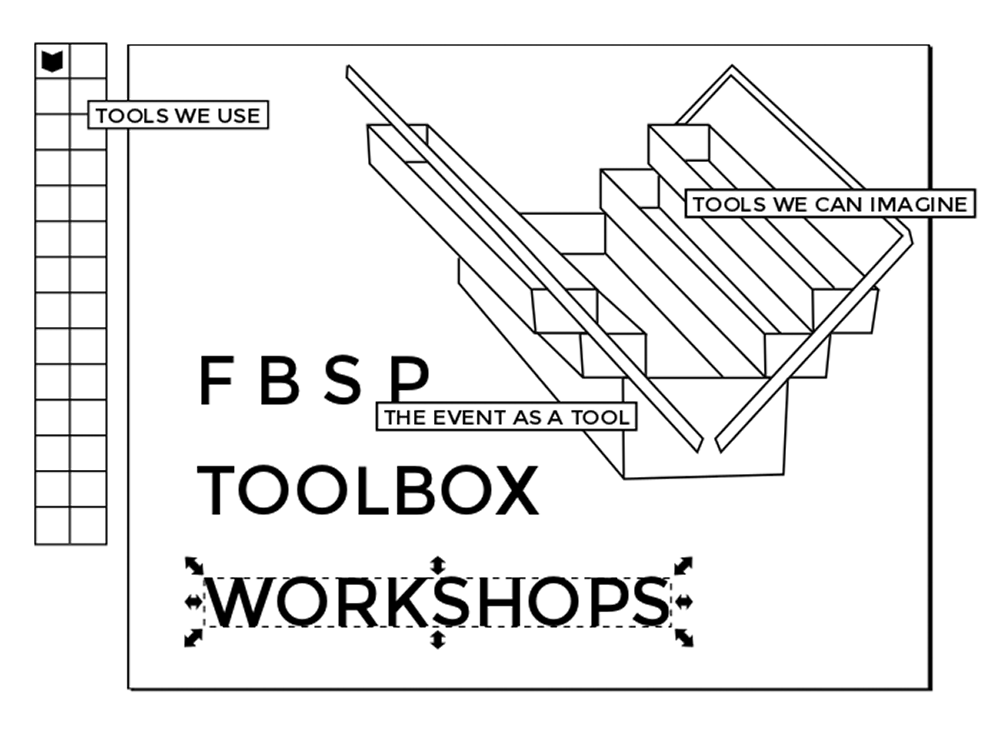

client

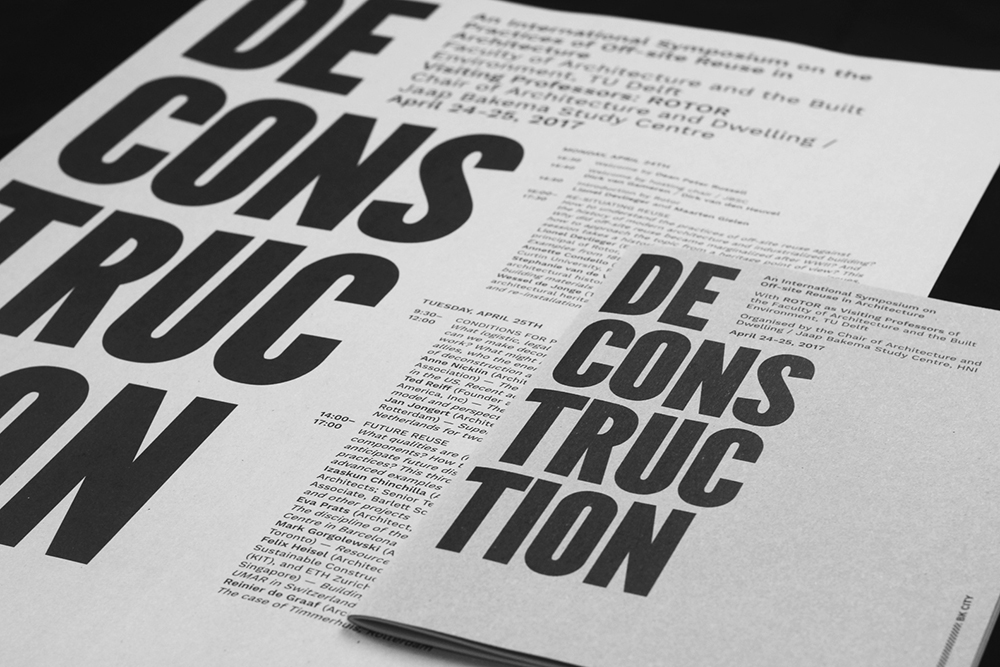

Loraine FurterI’ve been working on the identity and website for a conference. Since it’s a one-time event, you have more space for creativity. The event was on the subject of deconstruction, and was organized by Het Niewe Instituut in Rotterdam. They commissioned a Belgian architecture group called ROTOR, who work with deconstructed elements and reuse issues in their practice. It was actually my first official commission in which I would use my own web-to-print tool, using the browser to produce output. The website was very intuitive. Visitors could play with elements and move stuff around. And they could generate their own program for the conference. The coordinator and curator of the event wrote me an email at one point telling he really liked how I structured the code on the website. It appeared he actually read my source code by simply using the browser inspector. This showed he was interested in the technical aspects of my work and the way in which the website was created. I usually don’t encounter a lot of resistance, maybe because I’ve been working with amazing clients, but still, it was very flattering to get such comments. In short, I see the potential for a lot of exciting projects and I feel the influence of code in the field of graphic design is going to increase.

Design Work

Michael KryenbühlA student at HfG Karlsruhe created an open-source software for vector editing in a browser. Although it was not intended to be an alternative to Adobe Illustrator or similar software, it raises questions regarding what you might actually need and what is missing. More importantly, about how software might function differently. I think it’s less about an actual alternative software that will replace the standard everybody is using, and more about raising awareness about how it influences your design work.

solution

Petr van BloklandIn terms of project management, if you work on a prototype showing most of the design and technical solutions, and the final product needs to be ten times faster, or a more reliable version, there is no clear boundary between designing and producing. You slowly go from one aspect to the other. How should you define your role, and know when to hand the project over? If you want to do all the design work, it would mean having to do all the production work as well. My way of dealing with it is to write a program that does the production, because I’m not going to spend 80% of my time doing that.

client

Loraine FurterTo be honest, I have the feeling that clients respect the coding part more than the design work, because they simply don’t know how it works. It seems so complicated to them and they don’t have any expectations on that level, as compared to say, a logo, which is very tangible and could theoretically be finished by the next day. In terms of coding, I have the feeling that clients trust me regarding the amount of time it requires, but again, I might just be lucky in this respect.

Tancrède OttigerWhen I make an offer, I always integrate the development from the outset. I usually draft an initial budget and then I meet with the client to see if they are willing to invest that amount. Romain and I have developed templates for quotes over the years that include many parameters because our projects were becoming so complex that a basic offer was not sufficient anymore. The more precise you are at the beginning, the more time you can spend on the design work once the project is up and running. Usually the offers are pretty balanced between the development and graphic design aspects. The fact that I have done quite a bit of coding puts me in the position of being able to handle all the project management and client meetings.

Yehwan SongI think I will. I still love doing animation, and it’s not that different or separate from my web projects. When I design a website, I need to create other visual material, such as icons, logos and animations, so I don’t feel like I have stopped doing static design work. All the more so these days, in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, all the exhibitions happening in Korea are going online. An exhibition requires general promotional material in addition to a website. Therefore, I’m doing quite a bit of identity work along with the online exhibition platforms. I have heard that some traditional graphic designers have gotten frustrated during this crisis, because clients are now tending to opt for websites instead of books. They don’t want to print books anymore, because it requires more money and time.

Design Studio

Ted DavisI don’t think we have seen the wave crest yet. I hear that, in the US, coding is being introduced at earlier levels, from elementary school and junior high, on up to grad schools. I know that there have been initiatives in Switzerland to introduce elementary school teachers to some code logic and fundamentals, but I don’t think the shift has quite happened yet. Over the last four or five years, it’s been no problem encouraging a third of our students from the first-year undergraduate courses to select this field of study. They are seeing more and more creative code, and more design studios are coming out with identity projects and works based on creative coding. It’s becoming easier to show students and justify that this is a skill that you can use. The graphic industry is looking for people with this skill set. Still, I rarely encounter students with coding experience arriving in the first year. So we have not quite arrived, in that sense.

Jeroen BarendseAs a graphic design studio, budgets for media projects are in general a bit higher, but you also need more skills. You can hardly do them on your own, at least the things that we like to do. You require a designer, a creative coder and a programmer, instead of having just one person working on it. I’m pretty sure you can streamline all those things, and make them much more efficient, but we stopped doing that because we just want to provide the nicest work we can.

Mitch PaoneI just kicked off a project. We’re doing a branding project for somebody else and the whole thing amounts to the creation of a tool, that’s it. We give them a tool for them to make the stuff, and they’re going to have all the license to play with that within the guidelines of a strict sort of art direction that we develop. I also had a good discussion with Meg about this. From a business perspective, for a design studio, it’s a really interesting thing, because if you think about type foundries licensing fonts, if you create elements subject to intellectual property on products for specific companies, there is the possibility of this becoming quite lucrative for designers and design studios. This way, you’re not just dealing with the initial budget, it’s more like, “Hey, you own this for maybe two years. You can license this sort of thing from us for this period of time, but after that, it’s fair game for us to use on anything.” So you’re thinking about this more the way you would for music licensing or font licensing, as an approach for a business structure, versus a project-to-project fee. This could be really, really interesting as well as a really intelligent way to approach a design problem.

solution

Ted DavisI am the wrong person to ask, mainly because I don’t do a lot of commission work. It’s a big question as to whether code-based solutions are more of a suggestion coming from design studios, or if the clients are coming in and specifically requiring it. I just don’t know.

Graphic Design Projects

Tancrède OttigerAll of my graphic design projects began with my questioning the technical boundaries of what the developer could accomplish. Perhaps a part of our job is also to encourage your collaborator to embark on a quest with you. Also, it must be said that programming is a veritable black hole in terms of time. It is impossible to get paid for the actual hours required for most jobs. So it’s essential to work with people that share your commitment and feel the same way, otherwise I wouldn’t be comfortable.

Specific Projects

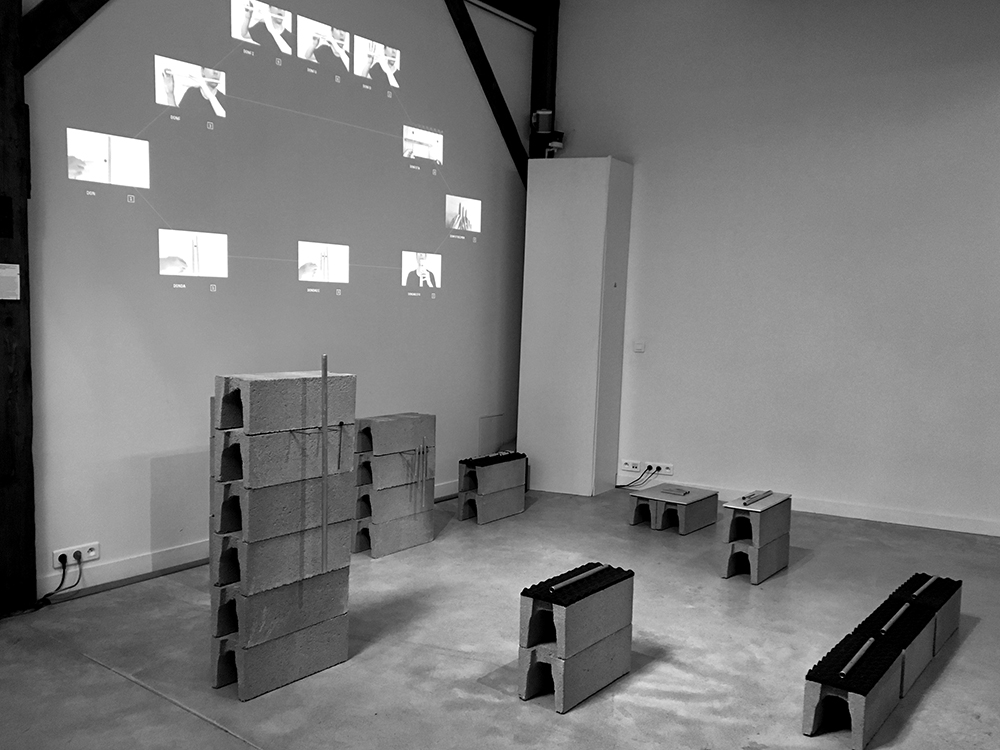

Jeroen BarendseThese are interesting things that we want to explore, but we also want to have fun doing it. We try to develop super specific projects for one particular event or space, and they are often very hard to document, since they’re only suitable for one moment in time, and one specific place. It’s not necessarily as eye-catching as what you might see on Instagram, and not immediately understandable. Exploring ways to document these projects is fascinating.

client

Sander SturingAt first my task consisted of making an existing design easier to use, or quickly create a lot of variations of it, but now, for the last couple of years, we have actually been designing with code. We’ll go into some specific projects later, but to give you an idea of our working method, we sketch a lot, we have always done that. We don’t think about just three or four specific directions, but explore all the directions we can think of. Then, together with the client, we see if there’s something they like, or they dislike, so we can develop the sketches. We used to sketch on paper, with very traditional graphic design tools, but, over the last years, as we have shifted towards motion design, we began using that, along with scripting, in the early phases of our projects. This way, we can demonstrate the upside of using these technologies to our clients. That’s a big change for us, but it’s really interesting and raises a lot of questions.

Design Projects

Ivan WeissThis is a super important topic for us. We worked with Adobe software for a long time, but we began to work more and more with other tools and to take a look at what else was out there. With book design projects, it is still much harder to avoid the standard Adobe software, as opposed to working on web-based projects. With web-based projects everything you need is more or less open-source, and the communities around that are quite strong.

Experimental Project

Samuel WeidmannFor our final BA project, we teamed up to do an experimental project, without caring about whether it would work or not. Basically, we decided to create a machine that could replace us as graphic designers. We thought it was kind of funny, since we were reaching the end of our studies, to develop a machine that worked as a graphic designer. We had no idea on how or where to start, because there were so many questions.

research

Jürg LehniAround the time I left ETH, I began working with my brother Urs, who was studying graphic design in Lucerne. In 1999, he was working on a collaborative thesis project: the creation of an ephemeral space for graphic design run by artists called Transport. They were granted the use of a shop for a few months before it was going to be torn down. They used the space to host exhibitions, events, lectures and parties there, and produced a lot of ephemera around these events. It was a very experimental, playful research project, and questioning and creating their own tools played a key role in their approach. I helped them create an interactive experience with a CD-ROM called Visomat which explored and documented their experimental project, and also started working on small software design tools with them. As I look back, I think a lot of things evolved out of that period. The idea of collaborating with graphic designers started there as well. It became much more exciting than just doing stuff on my own with a computer. Having a dialogue with somebody with a specific need, or a challenge, or some questions within a field, was a great starting point from which to develop my skills and my curiosity about this way of working.

typeface

Mitch PaoneSo, to answer more specifically about our projects, there are a lot of cases in which we’ve used coding to help us enable a lot of things, but in different capacities. Sometimes creative coding is a very expressive part of the work, or it can be very functional. I’ll talk about a few different paths we take. There are two projects, for example, both for Squarespace. One was a brand identity project we did for them: custom typeface, the whole visual system. Then there was also an exhibition piece that we did for this thing in London called Secret 7″. That was a bit more of an experimental project where we used creative coding. I’ll start with that one, because chronologically, that was the first project we did.

Visual Output

Ali-Eddine AbdelkhalekI think you have to expand the scope of it if you want to see any sort of momentum, and also this should include everyone practicing visual arts, not just graphic designers. However, it is true that, at least in Europe and the US, that there is an increase in the use of code or the hacking of existing apps in order to create new types of visual output.

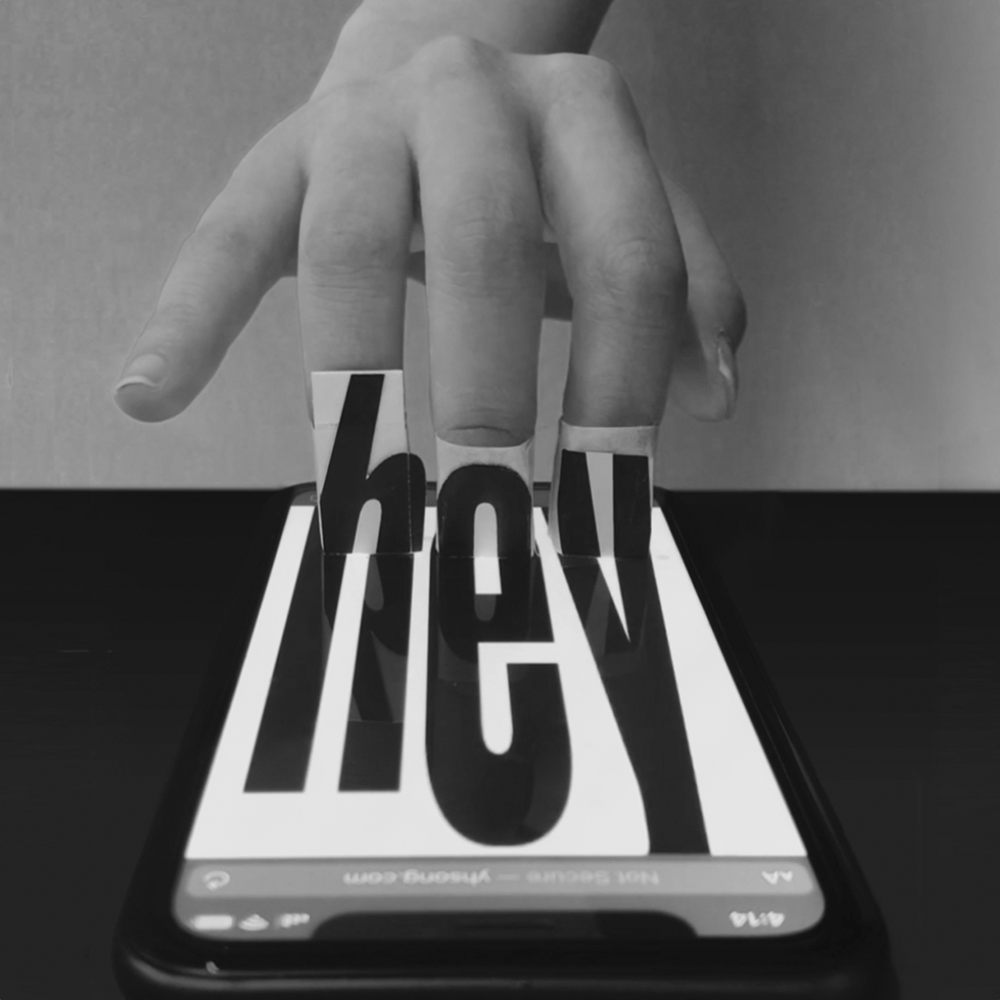

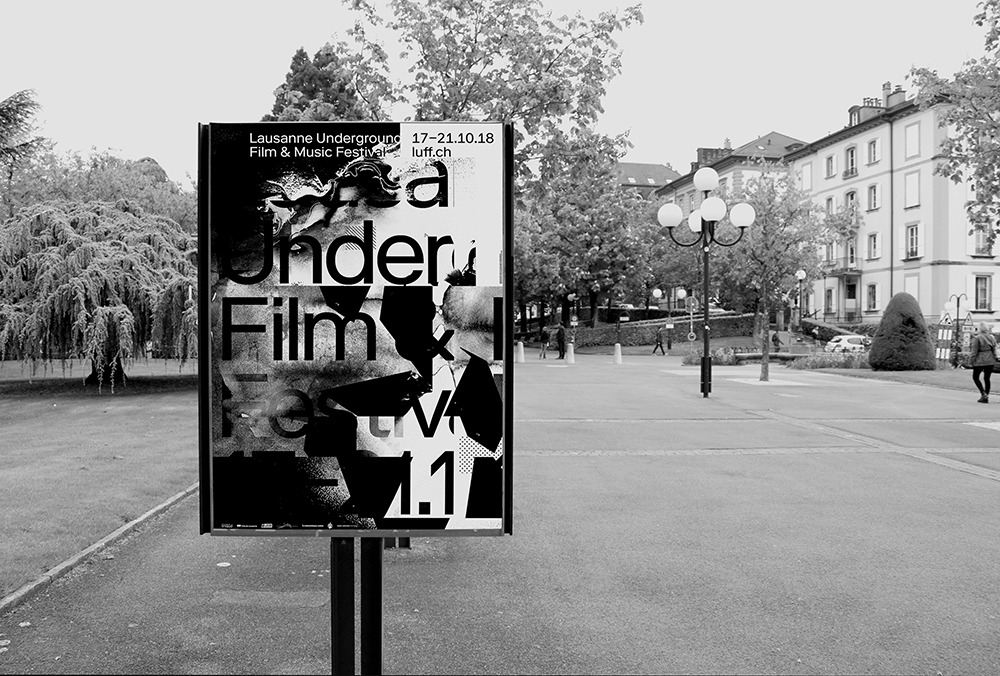

Ali-Eddine AbdelkhalekWe didn’t specifically set out to use creative coding or hack an application in order to obtain the visual output for the festival’s identity, rather we were trying to adopt the mindset of the festival. They gave us total freedom to come up with a proposal, in keeping with the festival’s experimental approach to the fields of music and the visual and performance arts. Les Urbaines consistently seeks to highlight emerging artists that are not yet established. They wanted a visual identity that was on the cutting edge of what one could do in terms of form. For the first edition in 2017, we didn’t use a traditional creative coding solution, but rather opted for a smartphone application that could distort the input from either photography or video sources. We began with images by artists that had been invited to participate in the festival, transformed them, using them as the DNA of the projects. We then used those distorted images for the poster, the brochure and the website.

Michael KryenbühlOne important thing in that regard is that often the clients are not really aware of what they actually need. They often approach us with a request for, let’s say, a poster. Then, while we are working on that, it becomes clear that additional social media elements are required, or even a complete visual identity. To give you an example, Stube im Progr, an open space in Bern, asked us to design their visual identity. They paid us for the identity, but we produced a tool for them with which they could produce visual outputs on their own, posters and flyers mostly. We simply used a part of the budget for this tool, to enable them to independently produce printed matter. Consequently, in the end, they paid us for something different, but we managed to work on the project in our own way without feeling like we were not being paid for the coding part. We simply used a different working method in terms of our energy and budget. This approach has worked out well in several cases, with a variety of clients.

Raphaël BastideThe most difficult part is getting them hooked on programming. This generation is very prone to expecting fast and spectacular graphic results. That sort of instant visual gratification is difficult to achieve with programming. I therefore try to steer them towards methods for quickly obtaining a visual output, then, once they are hooked, we can begin to talk about the processes, choices and semantics of creative coding. Initially, students are afraid of coding and of not being able to make nice stuff.

Ivan WeissThis treatment of typography changed the whole identity and became a central part of this project. In the final analysis, these multicolored typefaces and strange typographical shapes, readable or not, really influenced the tool we used for all visual output. Doing this in InDesign might have been possible, but not as quickly and easily as in the browser.

Loraine FurterOn the other hand, switching between different tools does something to tweak your style, and I very much welcome that. I think there’s an inherent richness in the collaboration between human designers and the software. It is also about surrendering control. I experienced this particularly when working with EPUB s. You have to give up some control since the user of the EPUB can change the font size etc., thus altering the visual output. This can be difficult to deal with for a designer. Such interactions generate both frustration and excitement, but I find it all very interesting. The EPUB adds a new layer of complexity to the designed interface because there is a third player involved, the user.

Identity Work

Mitch PaoneThen, to top it off, they are a massive brand who essentially took a big risk on a new way of thinking. For us, it proves, especially in the context of American corporate identity work, that this is the way things are going to go, but also I think it changed our perspective and it’s how we want to work moving forward.

Visual Language

typeface

Michael KryenbühlOne good comparison is the way in which we deal with type design. If we would estimate the value of a custom-designed typeface that the client didn’t explicitly request, what would we charge? 50 per cut? Or 20,000? We put a lot more energy into the design than we could possibly recover in charges because it is custom-made but was not commissioned as such. Still, by viewing it in perspective as a tool that helps us define and shape a visual language, it becomes less important to charge specifically for that work. Again, the typeface becomes part and parcel of the process, much like coding, all of which helps us find the right visual language for the commissioned project in question.

client

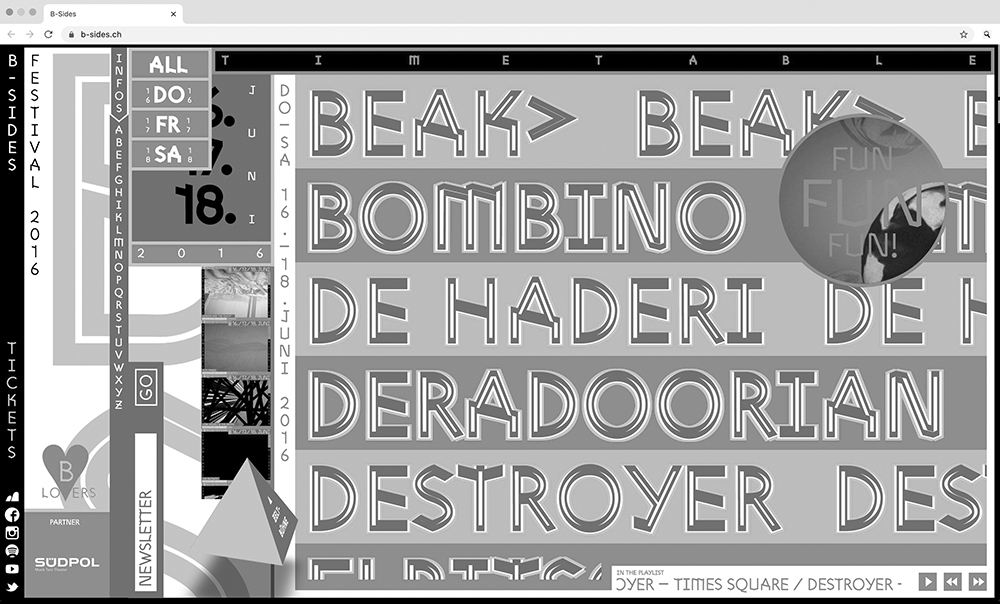

Michael KryenbühlWe are very grateful for the projects where we can really explore new techniques and working methods, such as for the B-Sides Festival website, for example. In that project, we knew beforehand that the available budget was low. However, all the people involved in the organization are equally paid and equally committed, so we chose not to count our hours. The budget often doesn’t necessarily relate to the amount of work you put in the project in the end, but is instead more of an investment in the exploration of new things and the ability to test them in their applied context. In this case, the payback didn’t translate into money, but rather visibility and the chance to learn new tools. You could say there was a monetary payback at a certain point, since we received a Swiss Design Award for that project. That was great, but it is, of course, an exception to the rule. However, from that moment on, in terms of commissions for projects for new clients, we began receiving the proper amount of money required for building a website. This then influenced the way in which we work: we didn’t see tools as an additional commodity for which we would charge a specific amount of money, but rather as an integral part of the design process. Conceptual sketching and coding goes hand in hand. A custom-coded website becomes a tool with which one can develop the concept and visual language of the identity, for instance; the entire creative process is intertwined.

research

Pierrick BrégeonIt was Clement who first came up with the idea to use a smartphone app to create visuals. I don’t remember how he got it, but, ever since the first festival, we have used a similar working method and we also began researching other means of creating visual languages. He was the one who pushed the limits, and now this defines us as a studio. Basically we don’t want to recreate what we have already seen. The smartphone application was a good way to avoid a well-known design approach done with common design software that everybody else is using.

Visual Identity

Mitch PaoneThis is actually a really delicate issue. We ran into this recently because we just did a brand identity for the Adidas flagship stores. We created the visual identity, and all of the assets for the system. Another company was tasked to convert that into code, and develop different systems because the formats were so cumbersome.

Pierrick BrégeonOne premise we consistently kept in mind over the three years we worked on identities for Les Urbaines is that we wanted the visuals to be visible from a great distance on one level, but we also worked intensively to create a detailed layer that revealed itself when you observed the visuals up close, creating a second layer of meaning. One other point I would like to add: two out of three tools we used to create visuals for Les Urbaines were smartphone applications. This enabled us to create the visuals with our phone, which is practical in a way, because we three are not always working at the same place and time. All these applications were free and were created to generate selfies. Integrating the use of selfie applications in our designs was another interesting aspect for us. It was a way of drawing attention to the question of identity through the visual identity of the festival itself.

Pierrick BrégeonSince we were dealing with up and coming artists who are often premiering at Les Urbaines, more often than not, they had no representative images. Consequently, we also had to create those. In addition, the images we received from participating artists were all quite different. As a result, our renderings also played a unifying role. What we did over the course of three years was to try to create a visual identity that could transcend itself. We used a very basic symbol, the first letter of the word “Urbaines,” as the main placeholder for the identity. When you see a “U”, you think of Les Urbaines. That was key. Then we set out to blend several identities into that one visual. This is a concept that is resonant with the question of identities presented by the artists at the festival.

client

Tancrède OttigerOf course. When I work with a developer, I bring them in at the very beginning to see whether they share my graphical vision, even if it may not be very clear at that stage, to see how we can experiment within the context of the project. However, developers don’t automatically join me in client meetings since, with each project, I first have to work on an extensive visual identity trajectory that I have to work out on my own. Then, as soon as we enter the digital phase, the developer I’m working with is integrated into the project and connects with the client.

Stan HaanappelWhat we offer and what we can invoice is a kind of grey area for clients, and also as a studio. Clients want a visual identity, and generally they don’t want to pay for a crazy amount of hours for us to develop a tool. We have to figure out how to demonstrate the value of such work. We now have a few projects that show what unique things these custom tools can do, so we can use them to convince new clients as well as to position the studio. I think it will slowly become the new normal, and that it’s something that’s here to stay.

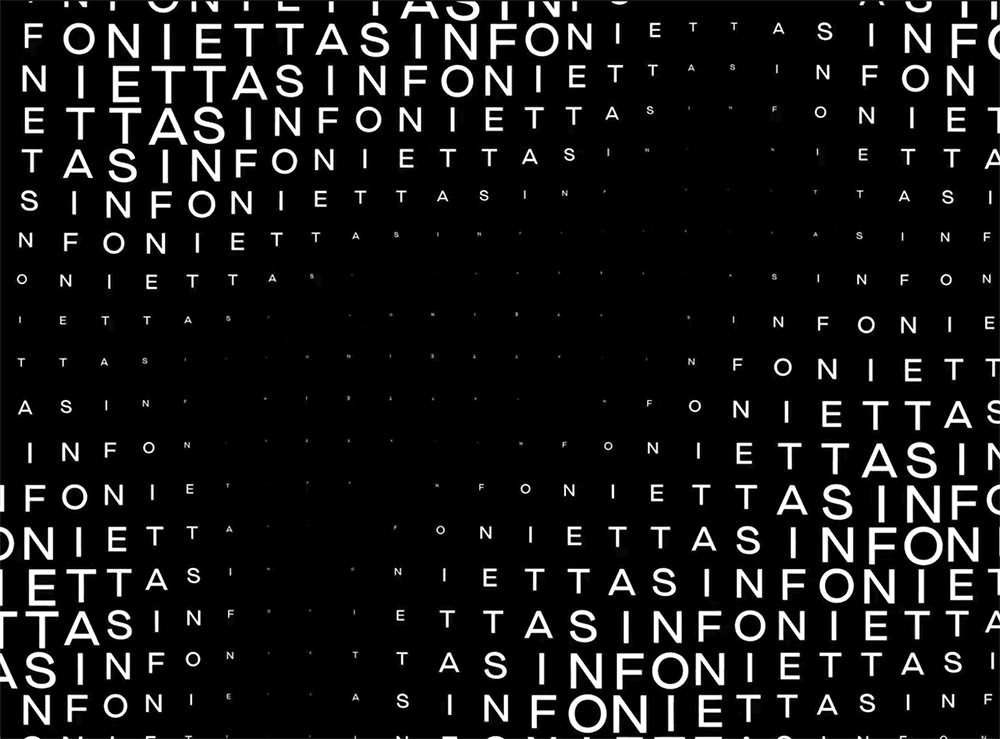

commercial

Stan HaanappelYes, we also wanted to talk about Cumulus Park, an innovative commercial district in Amsterdam, which was the first corporate, big client project for which we developed a custom tool. Back then, the way we had been working was to start out with the designers sketching ideas, and then involve motion designers and creative coders in a second phase, but in this case we decided to include a motion designer on the team from the very beginning, since it made sense for the project. The result was a sketch in motion that became the entire concept for the visual identity. We also had to make a tool that would be ready for another studio or designer to use to generate visual outcomes, so we weren’t developing a tool just for our team. We had to design it in a user-friendly way, so someone outside of our team would be able to use it independently of our process and our knowledge. The DEMO Festival and Sinfonietta tools were kind of rough, but this one had to be stable and refined enough so that someone could rely on it and effectively work with it, without having to get into the code.

generated

Léonard MabilleFor one year, we worked on Villa Noailles’ visual identity. We designed their website, posters, books, etc. Villa Noailles organizes a lot of events throughout the year, notably a fashion and photography festival, as well as exhibitions on design and architecture. One of the first PR items we created was a small website, a landing page for the call for applications for the fashion festival. We then decided to build the identity progressively. We developed smaller modules as part of the identity, basing the typography on a font by an American marine engineer from the 1960s. Antoine built a type tool that generated a custom type family from that open-source lettering program.

Creative Director

client

Sander SturingI was always doing a bit of coding, but it mostly wasn’t part of our work. A few years ago, we started focusing on motion design. We already had a motion designer in the studio and were incorporating a bit of animation in our projects at that point, but it had never been our main focus. We perceived a growing need for more dynamic elements from the clients and brands we worked with, so we started talking about it in the studio. Our creative director, Liza [Enebeis], always says static is no longer an option, and we truly believe that. Now, you have to design for screens of all sizes and animate things more than ever. The studio is now based around that idea, with two recent hires being motion designers who also work with 3D and VR, for example.

impact

impact

Erik van BloklandBasically, Google dusted off a method of font compression used to make files fit on floppy disks. This only makes sense if you’re Google , serving billions of fonts a day from your servers and wanting to harvest data in the process. It’s a huge investment for them to make these files available at all times; in addition, if they are a bit smaller, it has a huge impact on the cost in the end.

Type Design

Raphaël BastideTo draw a parallel with a different project, I am part of Velvetyne, an open-source type foundry. The quality of a font was a core issue when we created this foundry, and we wanted to redefine what a good font was for us. This was at a moment when big foundries were all about the technical, esthetic and commercial aspects of type design. A good font had to be beautiful, have many weights, be easy to use, sell well and also be well positioned vis-à-vis the history of typography, essentially centered on the end user to a large degree. We wanted to shift the attention to the designer and asked ourselves, “What can I do with a font, both as a designer and a user? Can I own it without paying for it? Can I redistribute my modifications?” The quality was not determined so much by the esthetics, but rather by the history and all the variants of the font, its timeline and how many designers had worked on it. All these issues refer back to the quality of the drawing that I mentioned earlier.

Loraine FurterI will give you an example to illustrate why it’s so important for me to use these basic programming tools. I started up a repository for open-source, free-license fonts designed by women or anyone identifying as such [www.design-research.be/by-womxn]. At first it was only for my personal use because I needed a tool to highlight these fonts. I took it upon myself as a personal challenge to only use fonts drawn by women, because they are so invisible in the male-dominated fields of typography and type design. Consequently, I built a website to showcase these fonts, and because it was open-source and looked nice, I thought I might just as well put it online, since others might also be interested in this collection. Now it’s one of my most well-known projects, and it’s a super simple DIY web page created with HTML and CSS , and free of access thanks to the source code on Git Lab.

Fabiola MejíaSome, like the TypeMedia Master’s program at KABK, use approaches like sketching, creating type by hand, and teaching how software works from a technical standpoint. DrawBot is a very useful tool for teaching font-related code basics. It’s a software that helps you understand how you can create graphical shapes with Python . It helps students to understand how the back end of type design works in a fun way. You can easily animate shapes and later translate them into a font editor like Robofont. You can play around without directly relating your experiments to defined typographical forms. As for Glyphs vs. RoboFont , it is a question of having two different tools, depending on your interests. Glyphs is easier for designers that are not that into scripting and RoboFont enables you to create your own extensions and scripts to support your type design tasks. Neither is better than the other, it’s up to the user to decide which one they prefer.

Loraine FurterYes, absolutely. I wrote a text in French for a conference recently about how, especially in the 20th century, digital design tools enabled women and people other than upper-class white males, who previously had enjoyed little acceptance in the design sphere, to find a backdoor entry of sorts into these professions. This phenomenon is particularly striking in the area of type design, where I noticed that, until recently, female designers were really difficult to identify. When I researched the history of the invention of the printing press, I found that women had been increasingly cut off from publishing from that point on, despite their involvement in this activity throughout the Middle Ages, during the manuscript era. Graphic design quickly became a male-dominated profession, and this status quo that has lasted until the shift to digital tools. At the beginning of the 20th century, women were hired as underpaid workers in type foundries to do typesetting work. They were indeed present but were excluded from the group of main designers.

Petr van BloklandI use Python as a programming language. It was created by Guido van Rossum, the brother of Just van Rossum, who is a good friend of mine. Just and I were looking for a source code to connect to the old Fontographer . I started out with some other languages, but then Python emerged as a really good solution. From that point on, connected to Python , Fontographer became RoboFog . It became the scripting language for many type design tools, like Fontlab and Glyphs , for example.

Fabian HarbYes. Almost all the tools we have developed so far are accessible. Font Gauntlet, our tool for proofing and animating variable fonts, is a web-based application and accessible to everyone. The more general type design tools that we have developed are documented on a website we call the Dinamo Darkroom, and people can download them from Git Hub. In general, whenever a tool seemed to make sense to others besides ourselves, we share it. It is very exciting to see what others do with your tools, how they perceive them and what kind of bugs or mistakes they might find and report to us. That is really rewarding.

Petr van BloklandI have been teaching Graphic Design at the undergraduate level at KABK since 1986, and also teach through the TypeMedia master’s program in type design. I also taught in the Graphic Design master’s program at the St. Joost School of Art and Design in Breda for about ten years, but I quit in 2017. I still do some workshops there during the academic year. We replaced our teaching positions with an online study program that we also started in 2017 called DesignDesign.Space.

Petr van BloklandNowadays, most of my days are filled with type design. I was lucky enough to be published in the Adobe library: that means my fonts were automatically distributed among 20 million Adobe software users. This helps, financially speaking. In the past, you were paid for a type license and people still think that’s the way the business model has to be shaped. The reality looks more like the Spotify model, where people download or activate fonts from a library, and the number of times your font is activated generates some kind of income.

Petr van BloklandWe organize Latin type design classes for Chinese type designers, hold workshops on variable fonts, courses on toolmaking, the design process, or, for example, the relationship between type design for print and online, and so on. We are currently organizing a 72-hour TypeLab marathon, hosting online lectures, workshops, demos and experiments with type and design. It’s a very diverse group which also provides an informal way for professionals and students in the field to connect.

Variable Fonts

Fabian HarbCurrently, this depends a lot on the environment. If you are a designer working with specific software, you can have full control over all these features. However, if you are “just” a reader of a news platform, at the moment there isn’t much exploration of the variable font technology available for you yet. I am sure this will change and things will open up, and that personalized settings and reading preferences will eventually be available to everybody.

Erik van BloklandWhen technology becomes cheap enough to be widely available, it is no longer confined to the people who can afford it, or the scientists that developed it, but moves into the hands of people with crazy ideas and spare time, along with a willingness to experiment, unfettered by the constraints of big projects. I see the same thing happening now with variable fonts. I’m pretty much on the side of the people who built this technology, the ones who know all the ins and outs of it and who are focusing on solving specific problems. However, there are new, young designers who don’t really care about that, and just use it for animation, to make typography jump and explode. Fantastic stuff is being done with variable fonts that is totally different from its original intended use, very different from the idea that resulted in the creation of the format.

Jürg LehniThe variable font file is, in and of itself, just a tool. It’s a way of making a lot of different weights. I think Petr van Blokland told me that the reason why variable fonts exist was Google , he was in touch with Google , and had heard that it could save them a lot of file space and bandwidth. Google has this whole Google Fonts repository of “free” fonts, “free” in quotes because when you use their fonts through CSS , and upload them directly from their server, you give them all your traffic information at the same time. It’s the same with the Facebook “like” button, right? Every website that places the like button actually provides Facebook with all their traffic information.

Jürg LehniWell, I think that there is a very practical reason for that. You’re scrolling through an endless feed of static imagery and it all begins to look the same. Then suddenly something is moving and, so of course it catches your eye. I think that this is how this whole kinetic type and variable fonts phenomenon became so big. It’s like playing tricks with our perception, right? It pulls you in. I wonder how long that will last. Perhaps eventually we will develop the same kind of numbness towards that kind of imagery as we have with normal static images. In Zurich, I’ve seen animated posters on big screens for exhibitions of art institutions. I was quite surprised. I thought, okay, now it’s arriving here. That means that you can do that as a profession. You will probably be busy from now on. However, eventually there is probably going to be a backlash. It’s eye candy, I think.

Jürg LehniI mean, variable fonts are to typography what responsive layouts are to print. Maybe we shouldn’t stop there, that shouldn’t be the end of the potential because it’s just interpolation. I think there should be way more than that. With computation, you can do way more interesting things than just interpolate between two extremes.

client

Fabian HarbThe question of how to make the public aware of new features so they can learn about the possibilities is a big topic. A lot of the time, clients are also hesitant about implementing new technologies, because they look at statistics that show that a share of their public is still using old browsers, for example. This makes them reluctant to move forward and risk using new technology. A few big corporations already use variable fonts in their systems, and on their websites, but in such a way that the user does not really notice the technology.

Fabian HarbSelling fonts the way we have done does not allow for much flexibility, consequently, licensing variable fonts has to be defined in a different way. At Dinamo, we fantasize about renting variable fonts. We could cloud-host files and allow the client access to them for the required amount of time, or for the lifespan of the project. This way, the pricing doesn’t have to be as high as when you hand over files for perpetual use.

typeface

Fabiola MejíaWhen you use variable font technology, you have a more interactive experience when you design typefaces, making typography a more engaging and responsive process.

glyphs

Jürg LehniGoogle ’s whole business model is of course based on data, and that’s how they get to that. Now, if they have a web font with lots of glyphs, supporting lots of different language scripts and different weights and styles, and you load the whole family, with all these files included, you are loading a consequent amount of data, in megabytes. If it’s a variable font, you only load outlines, and the rest is interpolated and extrapolated, so the file decreases in size. That’s why they invested so much money in it, apparently. That’s what I heard. I think this is interesting, because a lot of technology does come into existence in this very pragmatic way, and then subsequently shows some creative potential, and it is the designer’s job to find ways to have fun with it. The initial reason why variable fonts are here was not to make cool fonts move. It was just a possible solution for data storage problems, and to save money.

impact

Raphaël BastideI also think it is a bad move on Adobe ’s part to move all the software in their Creative Suite to the cloud. On the other hand, it triggers students’ interest in alternative software in order to avoid licensed software. They are extremely curious. They don’t use open-source software on a large scale yet, but they are curious and that’s really encouraging. Only now can we start to see the impact of Processing , which was launched ten years ago. The same people who are programming variable fonts today are the ones who discovered Processing back then. In my view, that’s a good sign of a seed that continues to grow.

price

Fabian HarbPeople also come to us with questions about licensing since you suddenly have a whole font family in one file. So, if somebody wants a file that contains a complete font family inside, what should be the price of it? For instance, the Weltformat festival used one of our variable fonts last year to create a nice interactive effect when clicking on buttons on their website. Variable fonts have a beautiful effect in this instance, but if we had not gifted them the license, the pricing on this would have been pretty steep.

typeface

typeface

Casey ReasIn that sense, the class is very much a general introduction, and it has become a lot less technical over the years. It includes less coding, but encourages the students to be original and inventive with the small amount of coding that they do learn. The class is very media-focused, so our students have a wide range of aims and aspirations. Some students are interested in video, animation, photography, typography, etc., so the class I teach on coding touches upon all of those subjects over the course of the term. For instance, we do a project that focuses on looping photographic images, almost like an old zoetrope, but integrating interactivity. We also do a project that allows them to load different typefaces and set them in a way that involves interactivity.

Book Design

Ted DavisOn the other hand, I’m a firm believer that code contributes to the evolution of the fields of design, typography, photography, motion, and book design. For quite a few years, we were limited to the tools made available, packaged software that offers so many possibilities, but also has so many limitations. The minute we introduce code, we break those limitations and can go into weird, uncharted territory. For me, code is really about expanding the realm of possibilities and confronting the limitations within the digital domain.

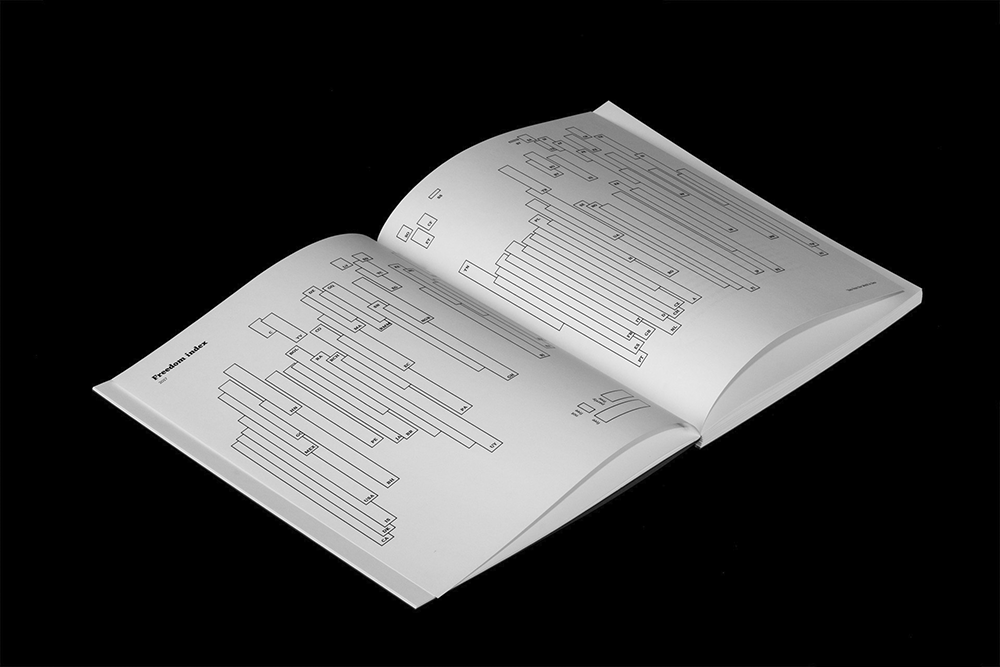

Urs HoferIt’s hard to say. I don’t know many LaTeX -produced books that have a “design-centric” approach. So it’s still a unique work. I wonder why LaTeX is not used more widely. You can often see that generated books deal with matter that can easily be generated, like long repetitive database dumps and lists. Nevertheless, particularly in book design, I don’t think there are many published books produced by code or scripts.

Poster Town Book

generated

Ivan WeissWe already had some experience with web-to-print tools and their limitations. Our first generated book, Animalia, was about all the known animals on planet Earth. We had to work with a huge amount of data there as well. We set up our own process from scratch, generating a PDF from our database directly through HTML . We then realized that this process made it impossible to work on small corrections after exporting. This meant you had to write exception rules in your script for each correction in order to avoid errors and export an accurate PDF, whereas these corrections could have been done in one click in InDesign . This was an important experience for us and helped us decide to generate the Poster Town book using InDesign , so we could manually execute small layout corrections at the end of the process.

Web Design

Emilie PilletI have a book which covers the basics, but the key is to have a project to work on. One thing I did was try and revamp an already completed project. If you build on something that already exists, you have a clearer idea of where you need to go. It’s a practical way to learn how to code. I also use printed matter as an inspiration for my web design. I think that there are so many things you can learn from the narration and hierarchy of print that you can translate into your work.

Yehwan SongI’m an art director, designer and developer currently based in Seoul, South Korea. My focus is on web design. I feel kind of frustrated when I see that most websites look pretty similar, even though they have very different content. So I try to change this, and make websites more content-focused. I really want to change the web as a platform, and try to push users to get the information they want, and understand that information.

Ivan WeissWe didn’t come into contact with coding during our time at art school. We had a web design course, but that was mostly about layout and wireframe design, not techniques and functionality.